You probably know that pseudo-science/pseudo-philosophy question about the tree falling in the forest. You know, the one that wonders if it made a sound if no one was there to hear it? We wrestled with a version of that question in our recent “Essay Writing for High School and Beyond” workshop.

You probably know that pseudo-science/pseudo-philosophy question about the tree falling in the forest. You know, the one that wonders if it made a sound if no one was there to hear it? We wrestled with a version of that question in our recent “Essay Writing for High School and Beyond” workshop.

If an idea does not affect the world, does it have any impact at all?

In the workshop, students prepped for the SAT essay exam, the Advancement Placement essay exam (“Good news, students. In this one, you get to write three essays against the clock. Won’t that be fun?”) and the college admissions essay. It was a great bunch of students. They worked hard each day and a few times they left needing a nap. Over the course of two weeks, students received feedback on at least eight essays. One of those essays was scored directly using the SAT rubrics and process so they could get a sense of where they would rate on that college admission scale.

This workshop enjoyed high demand, so much so that we had to cap attendance and then we let one sneak in after an impassioned plea from a mom. We will schedule this workshop again in October, see the Fall Schedule for further details.

But, back to falling trees and the impact of ideas…

In the workshop, we spent a lot of time focused on ways to develop ideas, both across the essay as a whole and particularly within paragraphs. These essay exams are geared toward testing critical thinking, an ability to work with concepts, tracing them from the abstract level into the details of real-world experiences or phenomena and back again. Students are expected to see patterns and argue the meaning underlying those patterns, demonstrating that the patterns exist with examples taken from a text or simply from their own experiences or observations. Two issues are key: 1) explaining the idea, and 2) showing it at work in an example.

With 11 students each writing one to two essays a day, we were able to identify three core problems in idea development:

Floating upwards – Ideas remain abstractions, never touching ground in the real world with concrete examples. A thought might receive some critical treatment, but only in the abstract, one concept contrasted with another on face value. Examples – or their shadows – might be mentioned along the way, but it is a “touch and go” approach, not a safe landing at a destination.

Floating down – Ideas are asserted without definition and the writer moves quickly from the abstract to a list of examples that are not developed. The writer presumes that the relevant point of each example is obvious and the reader is left to sort them out minus any details. Having exhausted his or her examples in the list, the writer has nowhere to go for the rest of the essay.

Floating sideways – Ideas come fast and furious in a stream of consciousness that does not stop to develop any one idea. The writer is no doubt intelligent and comfortable in the world of ideas. But, the reader is left to swim with the current in hopes of finding a concrete handhold somewhere downstream.

We addressed these deficits in idea development in a variety of ways. We gave them a model to follow as a template. Students were given back their essays with a paragraph identified for re-writing with that model. We also discussed strategies for developing examples and using them strategically.

We not only critiqued their writing, we focused on strategies for getting the building blocks of an essay onto the paper and then developing ideas. We find that students do not put enough effort into the pre-write phase of writing, that time when you are just brainstorming and looking for patterns in thoughts and examples. Mastering the pre-write phase is an integral part of success in timed writings, perhaps ironically so since you do not have much time to organize your thoughts. The faster you can get your ideas out of your head and organize them, the sooner you can assemble them into an essay. To just sit down and start writing against the clock is a recipe for a wandering diatribe that never develops an idea to its fullest. However, you have to embrace the pre-write as part of the writing discipline before you can do it quickly.

This hard-working group of students left bleary-eyed some days. However, they also got comfortable enough to help each other build ideas or flesh out personal experiences for a college admissions essay.

We hope to see them all again.

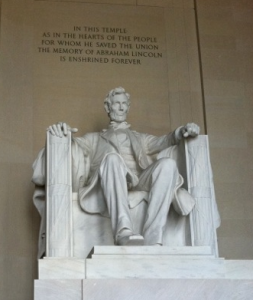

The president’s long lanky body swayed back and forth as the coach hit every pebble, stick and gopher hole on the road to Gettysburg. His massive hands held the quill and envelope tightly as he anxiously worked on the opening of the speech he was expected to give at the memorial ceremony in just over an hour.

The president’s long lanky body swayed back and forth as the coach hit every pebble, stick and gopher hole on the road to Gettysburg. His massive hands held the quill and envelope tightly as he anxiously worked on the opening of the speech he was expected to give at the memorial ceremony in just over an hour.